Remembering Floyd -

Stories

Two bricks is all she has left

All Hazel Albert has left of the house she lived in for 32 years are two bricks.

Most of what’s in her Rosewood home was donated or has been bought since 1999. Everything else, her diploma, her wedding pictures, all of it washed away when Hurricane Floyd’s floodwaters washed into her Pine Valley Road home behind the state Highway Patrol Office.

Her son, Cliff Albert, said that once police came to tell his mother it was time for her to leave, water was already covering street and that less than three hours later, the water was in the house.

“The water rose so fast,” he said, explaining that he and some friends were able to save his dogs, a couple small pieces of furniture and other belongings, but that most of the rest was lost.

“It’s nothing I want to go through with again. It was a nightmare. I was in shock, in disbelief. You know it’s true, yet can’t believe it. I had to start all over again. I’d accumulated a lot of stuff over those 32 years that I’d liked to have kept,” Mrs. Albert said.

But once the property was condemned and the FEMA buyout offer extended, she knew she had to move.

But first, she spent the next six and half months living at a friend’s house until her current one could be built, which meant a tough Christmas at her other son’s home.

“That was hard, because we’d always had Christmas at my house,” she said.

Even once her new home was built and she was moved in, things still weren’t the same.

“I had to start from scratch,” she said. “My first week out here, I was ready to leave. There were three houses out here. I looked forward to seeing the postman. It was so lonely.”

But with the help of friends, strangers and churches, she survived. One church on U.S. 70 East — she can’t remember the name — donated all of her appliances. Her church, First Pentecostal Holiness, took up collections for her and its other eight displaced members and offered whatever support it could.

“People were very good — people I knew, people I didn’t know,” she said.

But she never went back inside her old house. Cliff did, trying to save whatever items he could – enough times that he says he’ll never forget the smell of that old mold. But Mrs. Albert never did.

“I finally got to where I could ride by it, and then I finally got to where I could pull in the driveway, but I could never go back in that house,” she said.

Despite delay, she married

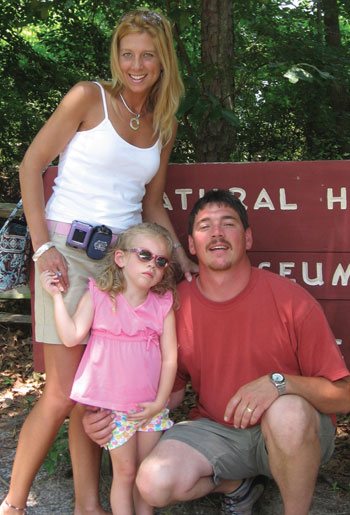

Ten years ago Friday, Michelle Pittman and Jeremy Singleton were scheduled to be married. But as Floyd’s floodwaters kept rising, Mother Nature obviously had other plans and their wedding was postponed until Oct. 2.

Today that subject is still a bit of a sore spot for Michelle, but she said, every year she and Jeremy, and now their 4-year-old daughter Anna-Marie, try to do something special to make up for it – like heading to the beach this year for a long weekend.

“Ten years later it’s still not funny to me,” Mrs. Singleton said. “It’s gotten easier, and I still can’t believe it all happened. But it’s been a happy 10 years for us.”

At the time, she was living in Goldsboro and her husband in Rosewood. She explained that after Floyd the only way they could get back and forth to each other was over the bridge by Cherry Hospital, but that on the day of her wedding, it, too, was shut down by law enforcement officials.

“We tried to go ahead with it up on until about 11:30. My wedding was supposed to be at 2 p.m.,” she said. “When my husband called and said he could not get to me because they had closed the bridge, I knew we weren’t getting married. It was just one of those things that couldn’t be helped.

“At 11:30, though, I knew it wasn’t going happen. Nobody could get there.”

Her caterer and wedding coordinator was in Princeton, her photographer in Walnut Creek, her fiancé in Rosewood and she was in Goldsboro.

But while her family tried to console her – “I was devastated,” she said – her future in-laws and her church were springing into action to try and reschedule all that they could.

“Everybody was happy to oblige. Thankfully it worked,” she said.

And the wedding went off without a hitch two weeks later.

“It just worked out very well. I was just very lucky. Everything clicked. And it’s been wonderful,” she said.

Despite loss, he was lucky

From a hospital bed in Raleigh, Chubby Bridgers saw what Hurricane Floyd had done to the stores he owned inside Barnyard Shopping Center.

His children had tried to keep the news from reaching him.

He was, after all, recovering from a major heart surgery.

“Our son Dale called up and said, ‘Don’t tell Daddy,’” Chubby’s wife, Lillian, said. “He said, ‘Don’t upset him. But the Cloth Barn is flooded.’”

So when Chubby turned on the news a few days after Floyd hit and saw images of his shopping center enveloped in water, it was a shock.

“He’s watching it and says, ‘My gosh. It’s the Cloth Barn,’” Mrs. Bridgers said. “Then he said, ‘Isn’t that the top of my big truck down there?’”

“My boys moved the trucks down there because they were afraid they would get hit by a tree,” her husband added, grinning. “Let’s just say trees didn’t end up being the problem.”

The family, because they did not have flood insurance, lost more than $1 million in inventory and several trucks as a result of the water that followed Floyd.

“I have never ever seen (anything like it) and I hope I never do again,” Mrs. Bridgers said. “Everything on the floor was gone. I mean, there was just nothing. ... You had to take down all the walls ... because you had to redo all the electricity.”

But 10 years later, Bridgers still maintains that he is lucky.

“As sick as he was, there was a different slant on it for us,” his wife said. “I got upset for about ... two minutes and he said, ‘Listen. I’m alive. All the children have got houses. There’s not one of them who is in ill health. We’re well off.’”

Much has changed in Goldsboro

The city of Goldsboro tore down 297 houses as a result of damage caused by Hurricane Floyd, but Planning Director Randy Guthrie said changes to flood ordinances and maps should prevent future catastrophes for local residents.

In fact, the most high-risk areas were purchased from FEMA by the city and development is restricted in them.

“Now, (the houses) are gone because they were flooded ... and we actually bought them out through FEMA, when it did its policy of, ‘We would rather take you out of harm’s way and buy your property so we don’t have to keep rebuilding it,’” Guthrie said. “I can’t think of any situations where we have an entire residential neighborhood in a flood plain. I can only think of instances where we might have some lots with flood plain along the back.”

Ordinance changes created that reality, he added.

“What a lot of cities did, they went back and looked at their flood ordinances ... and made them a lot stricter as a result of Floyd,” he said. “Here in Goldsboro, the toughest place to build is in the flood way. The flood way is kind of the central part of the 100-year flood area. So typically nothing is really done in the flood way.”

Even on the land the city acquired, Guthrie said, the only type of development currently allowed under the Stafford Act is for projects like soccer fields and natural parks.

“It allows for open space,” he said. “They don’t want you to build anything like bathrooms. They don’t really want you to build parking lots.”

The rules were changed to promote public safety in the event something like Floyd happens again.

But Guthrie did say that as development occurs in other parts of the city and region, revisions constantly must be made to the 100-year flood plain.

“We haven’t had tremendous residential growth since Floyd and in those areas, we would discourage it,” he said. “But every year when stuff happens in Raleigh or Smithfield or here, theoretically, it’s altering the dynamics of the water. That’s why they update the maps periodically.”

The maps are created by FEMA — based on intensive studies, hydraulic models and data analysis.

“What the 100-year flood plain means is those places within it have a 1 percent chance that they are going to have a flood over the course of a year,” Guthrie said.

And property located within it face the most risk if another major weather event were to unfold.

Still, he said there is always a chance that those living outside that area could see flooding after a hurricane.

“That is, of course, theoretical,” Guthrie said. “Something as simple as a clogged ditch — a tree falling in a ditch or something — could create flooding in other places.”

Mar Mac was ‘devastated’

Ann Moore of Sandhill Gas Co. said she was lucky, her Scott Hill subdivision not affected by the storm. At that time she worked at Jackson Builders and traveled down Old Grantham Road going to and from work.

“I remember how devastating it was in the Mar Mac community. You’d ride down the Old Grantham Road where most of the homes were flooded and to see as people started cleaning and see them tossing all of their belongings out on the roadside because practically nothing could be saved — it was a very heart-wrenching sight. It just tore your heart apart to see so many people in such devastation.

“It was just so sad and now all of those houses are gone. There is nothing there now.”

Mount Olive ‘was an island’

“As far as Mount Olive it was truly an island. My son was visiting from Ohio and he had to return to his base. We went every way from Sleepy Creek and no matter which way we went it was blocked. We had to go to Newton Grove. We talked with the truckers to find out their routes.”

Prior to that Ms. O’Donoghue said she and her son were in the house when they heard a loud noise. They wound up standing with a group of people near the road near one of the lake’s dams.

“The asphalt was bubbling up. It exploded and went up in the air then flew down the ‘river’ of Sleepy Creek. Huge hunks of asphalt were racing by. It broke through and took out the road, took out everything. It was like a visual out of some movie.”

As the road disintegrated the onlookers realized the danger and started backing up. Ms. O’Donoghue also realized that the collapse could cut the water lines. She and her son raced back to the house to fill containers with water.

People on the back side of the lake had to use roads normally traveled by farm equipment to reach the nearest road, while those living near Mrs. O’Donoghue could still reach Sleepy Creek Road.

Along with no water, power was out as well and Mrs. O’Donoghue recalls using an old-fashioned coffee percolator and cooking eggs and bacon on the grill.

“It was a mixed day and scary.”

A number of trees were down and neighbors gathered their chainsaws and trucks to clean up the debris.

In town, the chamber office suffered some roof damage and the carpet was soaked. Prior to the storm the office’s computers, monitors and other equipment had been covered by sheets of plastic.

“But business went on and people were out in the streets cleaning up.”

Rescuing people

Brandon Jones, paid Dudley firefighter and Thoroughfare Fire Department volunteer, was among the volunteers who staged at the Mar Mac Fire Station.

“We went out on boats trying to get people out of their houses — people who really didn’t want to come out of their houses, but were not left with much of a choice unfortunately. I was over there (at the Mar Mac Fire Station staging area) for three days. Yards were flooded so they couldn’t get out, and special needs folks we had to get the boat in and get them out. Most, I won’t say all, but most were agreeable. They didn’t want to go at that time. They just wanted to wait it out and see if the water would recede any. We made about three passes through every neighborhood just to make sure and we double checked the house and we had the National Guard out there with us, too.

“I had a friend who lived on Bryan Boulevard who lost his house and that was very sad. It was pretty emotional for everybody when you go to somebody’s house and you pick them and come back three days later and see how much the water level has risen and see all their personal belongings they have lost. It was pretty emotional.

“The water got up to the eves, a good 9-10 feet. I’ve never seen anything like it before and hope will never see anything like it again.”

The yard was lost

Doug and Judy Wiggins of Mount Olive are used to flooded yards — the section of Crest Drive they live on is prone to flooding and rains turn their yard into rapids before pooling on their neighbor’s yard. The house has not flooded even though the yard has.

However, the damage from Floyd was so bad that he had to haul in dirt, cut down trees and literally replace the yard.

“It took months to get it back in shape,” he said. “The water literally caught the sod, pulled it and flipped it over to expose the roots.”

‘Traffic was just slow, slow, slow’

“When we had to get items to supply the store we had to leave here go to Newton Grove and cut across to Smithfield then into Princeton and back through Pikeville to Goldsboro and it was an 8-hour round trip,” said Jim Grantham of Grantham True-Value Hardware. “It probably lasted for 4 or 5 days. It got a little shorter as the days went on. We didn’t have to go to Pikeville but it was something else. People on Hood Drive got flooded out it was just a horrible time for everybody. You just couldn’t get anywhere. It was not quite as bad as it was with Fran when the power was out. Don’t recall power issues at the time. Fran we were out for several days. Luckily, we had a generator. Floyd was tough to get things to sell.

“It was unreal the path you had to follow and then everybody had been detoured from four-lane and this big trucks on theses side roads. Traffic just didn’t so very well. Traffic was just slow, slow, slow.”

Getting the crops in

Billy Smith of Smith Grain Co., Dudley, had watched a crop of corn growing across the road from his office — a crop that held promise of being one of the best only to see the stalks bent to the ground by the storm.

“The Dudley area itself is fortunate to have one of the highest elevations between Wilmington and Weldon and the water here drains right off with no problem. Where the problem came in for me as a businessperson, is the grains affected by the storm that were blown down in the fields and consequently made low quality out of the corn a lot of damage rotten kernels. It took many months to harvest the rest of the corn that was out there.”

A building he rented in Mount Olive was town “all to pieces” and had to be repaired. Took two months to clean up where you could repair it.

“It affects it (business) even today if insurance companies find out you are east of (Interstate) 95, the insurance rates are higher in flood areas or they are scared you are going to get flooded out. I think that is unfair, everybody east of 95 did not get flooded.”

Smith noted that some of the older grain bins on the site weathered Hurricane Hazel in the early 1950’s. He said he thinks the rounded shape of the bins and the fact that they were filled with grain helped stabilize them in the wind and kept them from being damaged.

“I remember (with Floyd) trying to get in as much corn as possible before the storm and the bins were getting almost filled up. One farm still harvesting and I helped them unload until 3 a.m. one morning. They were still bringing it in and they called me and we were watching it (storm) on the computer in here. It started raining and they said, ‘well it is over,’ and we just had to quit and go home then. It was raining and it did not stop any time soon either.”

The commute was tough

“The biggest thing I remember was trying to commute back and forth to work, from where I live here in Grantham we travel probably in a 50-mile radius doing construction and painting work. Trying to get to our suppliers to get products was the biggest task,” said Mike Brimberry, self-employed and owner of Brimberry Painting and Construction, Grantham. And then of course when we got there in the building materials department not having anything because everybody was rushing to get the lumber, tarps to cover roofs… trying to get just enough materials to do repair work let alone trying to get job back in a 100 percent condition. Then all of the hubbub that went with it.

“The wind and rain did not bother me, but the aftermath…”

The Fair must go on

Floyd struck just weeks before the fair was to get under way. The fairgrounds has an agreement with Progress Energy to stage its vehicles on the large parking area at the fairgrounds.

“They moved in with a tremendous amount of equipment,” Milton Ingram, Wayne Regional Agricultural Fair Manager said. “There were even helicopters landing out there. We had a place out here where people were picking up ice and supplies, and of course we were trying to get ready for the fair at the same time.”

The helicopters, he said, were being used to map out routes for the ground vehicles.

Ingram who lives in Princeton had to travel down U.S. 701 from Smithfield to Newton Grove to get fairgrounds.

“I could stand in my old office and see the water down about to where the Huddle House is now. The flood subsided enough they moved back the emergency supply station uptown and Progress Energy finished with their stuff just ahead of the fair. We had the fair, but it was an abbreviated version.”

Ingram said he was caught between “the rock and hard place” — some wanted the fair to continue, while others said it would be inappropriate.

“A lot of family people were calling saying please have the fair because my kids need a break from all of this flooding. I had one lady who stopped by and she had her children with her, she said she brought them here to the fair to have a good time while her husband was pushing mud out of the house. I had another lady who came to the fair who had a little boy about three years old. She said every day they went by here going to his daycare, and that one morning he told her he was going to pray that we would have the fair. The lady who stopped and told me about her little boy, I needed that because I had gotten some ugly calls.

“It ran about three days and a whole lot of people seemed to appreciate that we went ahead attempted to have it so that they could get away from some of the misery that they had experienced.”

The fairgrounds itself suffered only minor damages that were quickly repaired by employees, Ingram said.

Crops lost

Rouse Ivey of the Summerlins Crossroads community, who was born in 1955, the year after Hurricane Hazel ravaged the state, said that until Fran and Floyd he had not really been affected by hurricanes.

He recalls hearing his father and other older people talk about Hazel, the storm by which all others were measured by for generations, and where they were when it struck. He said he did not understand that until his brushes with Fran and Floyd.

“I was 44 (when Floyd struck) and now when people talk about hurricanes my ears perk up like a dog’s. Since Fran and Floyd when they talk about hurricanes it gets my attention. Fran tried to blow everything away. Floyd blew and messed up some things, but it was the water that messed things up.

“It didn’t dry out the next week — we had fields that it took a month or month and a half before we could get back into them. There was so much water and the water ran so bad that it took forever to level the fields. It took all winter to do.”

His cotton crop that had yet to fully bloom escaped much damage. However, Ivey estimates he lost about 10 barns of tobacco because of the storm.

“Sweet potatoes — you can imagine what 20 inches of rain did to them They soured in the field, and the tobacco fields you couldn’t get to them.”

Rouse estimates that he lost more than half of his sweet potato crop.

“It was a maze trying to get to Mount Olive because all of the old ponds that flooded. All of the old ponds burst with those 20 inches of rain and it carried away the roads and water lines.

“Water was in so many places that it was difficult to get to Mount Olive, Goldsboro or Kenansville without having to back up and start over because of flooded roads.

“We forget how convenient it is to get in our vehicles and be in Goldsboro in a short time. Floyd made you realize how convenient it is.”

Nothing prepared them for Floyd

The Sutton family has farmed here for two generations and is familiar with occasional flooding. But nothing in those two generations of experience prepared them for Floyd.

“It ran me out of my house. It got under and around it, but did not enter. It got high enough to touch the floor joists. It rose pretty fast after the dams at Sleepy Creek and Walnut Creek were breached. We were just swamped,” said Wayne Sutton of Seven Springs.

“I didn’t think it would ever stop rising. I had never seen anything like that before and I hope I will not see it again. At the steps going up to the church on the hill (at N.C. 55) you could get on a boat and go all the way to St. John Church Road. One of those days before the water receded it was windy and I looked out and there were white caps out there. That was a mighty funny feeling to leave my house like that.”

At his son’s nearby mobile home, Sutton said “you could stick your finger into a vent and touch the water.”

The day of the flood, Sutton said he was leaving to feed his hogs when he noticed water was beginning to creep into the back yard.

“I went to the hog houses for about an hour and when I got back it (water) was almost to the corner of the house. I told my wife to call for some help, that we were going to move out of the house. Before we could get all the furniture out by about lunch time we had to drive through water to get out.”

The help came from the town’s Baptist and Methodist churches, National Guard and Seven Springs Fire Department.

“It was really heartwarming how the community came together. We had already helped some others in Seven Springs move, never thinking that we would have to be helped. There was a lot of helping one another. It brought the community together.”

Sutton, who farms with his brother Jerry, said they have one farm near St. John Church Road that took three months to dry out. The land is nestled in a little valley and water kept running from the higher ground and across the field.

The family lost close to 50 acres of corn and almost 200 acres of soybeans because of the flooding.

“All the corn had not been picked and the water touched the ears. No one would have wanted it if you had picked it.”

Not a smooth opening

Charles Ivey has been principal at Spring Creek Elementary School since the schoool opened, which was only a few weeks before Hurricane Floyd hit.

“That was our very first year. We had just opened,” he recalls. “We had established bus routes and before they got going good, we had to reroute them.”

Although there wasn’t much flooding on the actual school grounds, it was a major issue for buses traveling in from Seven Springs and LaGrange, he said.

“What sticks out in my mind, the bridge just below the school was washed out,” he said. “I had teachers that lived a half-mile from the school, that had to drive five miles around to get to the school.”

It was several months before all the bridges and roadways reopened, Ivey said, making it a “very exciting first year for our building here.”

Schools across the county were affected, most of it “an inconvenience” more than anything else, Ivey said.

Ten years later, the principal still has his planner from that first year. Pausing to consult the calendar, he calculated the time frame.

“The hurricane came Sept. 16. Actually we were out a whole week, all the next week. It looks like we were back on the 27th and then out on the 28th and 29th,” he said. “It seems I recall something very strange when we came back to school and then they were out two more days. Seems like it was another storm right behind it, that could have been the 28th and 29th.

“We came back the 30th, which was the first day of the rest of the year.”

Because of the effects felt around the state, Ivey said either the state board or the General Assembly made the decision to excuse more days that year, so districts did not have to make up all the days missed for the storm.

“It was really strange coming here that first year and facing that right off the bat, and particularly being right here at us,” he said.

Everyone pulled together

Micheal Lucas, former vice president of finance at Wayne Memorial Hospital, recalls both the challenges faced by staff as well as the unified efforts.

“I remember there was difficulty — some of the employees had difficulty getting to work because many of the roads were blocked and there were staff who spent the night in case others were not able to come in,” he said. “It took a week or so for the Neuse River to subside enough for traffic to come over the Neuse River.”

The National Guard also provided a “taxi service” for some of the staff, particularly nurses traveling from south of the river, Lucas said.

“That shuttle service went on for several days,” he said.

Lucas also remembers one night when the flood waters were really rising.

“Kitty Askins Center was beginning to flood and we took maybe 10 patients temporarily,” he said. “I don’t know if they actually flooded or took the precaution in case it flooded.”

While he couldn’t recall there being an increase in the number of admissions or injuries in the aftermath of the storm, other effects were certainly being felt.

“Obviously there were people who could not get there for lab tests and x-rays, maybe even some of the elected surgeries were postponed as well,” he said.

Food services also picked up the slack, preparing and providing a lot of sandwiches and items for the fire, police and public service employees working around the clock, Lucas said.

That same sense of teamwork was prevalent all over the county, Lucas said.

“I remember everybody sort of pulling together, came together, as often happens in a situation like that, whether they’re trained in a specific thing or not,” he said. “It was sort of a cooperative spirit among all the people involved.”

‘As public health as it gets'

For Carolyn King, health education supervisor at the Health Department, amid the turmoil she found much to take pride in.

“One of the things that stuck out in my mind, I don’t know why but it just made me so proud particularly of the way our staff responded,” she said. “Our nurses crawled on the back of National Guard trucks and went into places that you could not get in any other way to give tetanus and hepatitis 2 shots, because all the electricity folks were working on those power lines and in the muck and mud and the water, and they had to have those shots.

“To me that was as public health as it gets. ... They helped to staff the shelters and to tell you the truth, a lot of those nurses were in harm’s way –– nurses, social workers, helped people to shelters

Mrs. King’s family lived on the other side of the river –– the Westbrook Grove Church area –– so found it challenging just driving into town.

“Getting to work, I went to Smithfield to come to work,” she said. “I didn’t want to cross the river, I will be honest with you.”

A ‘labor intensive’ response

Evelyn Coley, director of nursing at the Health Department, recalls assisting with staffing four shelters around the county.

“Goldsboro is divided by the Neuse River,” she said. “Staff had to drive all the way up to I-95 and come up through Kenly if they wanted to come to work. So what we did was look at who lived on which side of the Neuse and staffed each of those shelters. Some people actually drove in going the long route.”

Part of their role was to provide tetanus vaccinations for victims of puncture wounds or exposed to the flooding.

“We did a lot of that afterwards,” she said.

Environmental health was also very busy once eating establishments reopened, as well as covering situations with septic tanks and wells, Mrs. Coley said.

“It was very, very labor intensive — the bulk of what we were still working on three weeks out,” she said. “People calling, complaining of illness, tetanus vaccinations. ... Then when we got back to work, we had a backlog of clients, that was very challenging.”

There was a lot of “telephone triage” and handling unique cases at the shelters.

“People had to evacuate their homes and they didn’t take their medications,” Mrs. Coley said. “We tried to work through their exiting pharmacies. DSS (Department of Social Services) was also involved because they staff them with social workers and mental health.”

In the midst of it all, the generator went out at the Health Department, she said. At the end of a particularly lengthy day on the road, she remembers getting a call one evening after arriving home and having to respond to the situation.

“So we transported our vaccines to Wayne Memorial. That’s where we store emergency supplies. It’s a pain to package all that up,” she said, explaining the process of having to identify and inventory every item.

There was a silver lining, though.

“The good thing is the amount of partnering, collaborating, you don’t think about ‘my agency,’” she said. “It’s a true community collaboration. Although it was traumatic for people to be displaced and have difficulties, from a community experience and collaborating, it was good.

“We’re just lucky to have the base and have a good working relationship with the National Guard; emergency services is like the gatekeeper at those times. Even though you worked long and hard and worn slam out, it was worth it. I guess it’s like this –– hurricanes and threats of disease, that’s when they realize the benefit of the Health Department.”

Students’ lives disrupted

Dr. Steven Taylor, superintendent of schools, was human resources director at the time Hurricane Floyd blew through the county. One of his responsibilities was the schools’ calendar, especially as students were sent home for several days.

“We have never been out of school for six days in a row,” he said. “We also had to deal with children that were displaced, make accommodations for them.”

While there may have been minimal damage to school buildings, the ramifications were farther reaching, Taylor said.

“The power was out, we had roads that were under water so we could not transport children,” he said. “We had families that were flooded out, lost everything they had. Some students were not able to come back so we worked with those families. Staff had issues coming back to work. ...

“It was disruptive for our children, for those children to come back whose families that had to experience physical loss, it was really hard for them to concentrate in school. But somehow we made it.”

For others, there was a great sense of relief and gratitude.

“Personally, it made us really thankful for the things that we did have, like power and water, the roof over our heads,” he said. “It’s just a memory and something we hope we not have to go through again.”

By News-Argus Staff