Meth: An old threat takes on new power

By Laura Collins

Published in News on June 27, 2010 1:50 AM

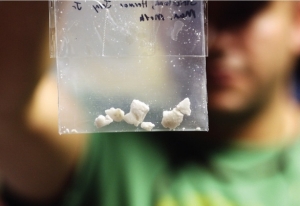

News-Argus/MICHAEL BETTS

Methamphetamine in rock form is held out by Wayne County Sheriff's Cpl. Chris Peedin, the meth lab investigator for the Wayne County Sheriff's Office.

News-Argus/MICHAEL BETTS

Wayne County Sheriff's Cpl. Chris Peedin looks at a house on Dakota Avenue in Goldsboro where he and his fellow law enforcement officers raided a meth lab. Meth labs within heavily populated areas are very dangerous because of the possibility of an explosion during the cooking of meth and the hazardous waste the operation leaves behind. Peedin said Wayne County ranked as the No. 2 county in the state last year in meth lab seizures.

News-Argus/MICHAEL BETTS

Pseudoephedrine, the active ingredient most commonly seen in cold medicines, is the main ingredient in meth.

In 2008, Wayne County reported three methamphetamine lab raids.

A year later, that number jumped to 24, earning this county the distinction of being No. 2 in the state for meth raids -- and the county with the largest increase from the previous year.

Similarly, Duplin County reported six meth lab arrests in 2008, but that number increased to 21 in 2009, making Duplin the county with the third highest number of meth lab raids, according to the State Bureau of Investigation.

Although officials differ on their opinions as to why there was such a dramatic increase, there is no arguing that meth has an overwhelming presence in the area.

"It wasn't the drug of choice so much five years ago," said Joyce Kelly, executive director of Blue Horizons Goldsboro Assessment and Treatment.

But the intense high, addictive nature and ease of access to ingredients created the perfect storm for a meth epidemic in the area, she said.

Making meth begins with a trip to any drug store, Duplin County Sheriff Blake Wallace said.

"It's increasing in popularity because the ingredients used to manufacture meth are readily available," Wallace said. "It's relatively inexpensive and has become the drug of choice. Plus the high is very intense and lasts an extended period of time. (The users) are getting more bang for their buck."

In May, Duplin County made one of the largest seizures of meth the state has ever seen. Wallace said 17 pounds of meth with an estimated street value of more than $1 million were seized, the largest in his career. It was found stashed in 14 horse saddles.

While there seems to be an increase of meth use in the area, Wayne County Sheriff's Office Cpl. Chris Peedin said it might have been just as prevalent in the past, but now area law enforcement officers are paying more attention to it now.

"We're more aggressively hitting it now, and it just seems like more," Peedin said. "It's been here for a while."

Peedin is the meth lab investigator in Wayne County and said so far this year there have been 10 meth lab seizures. He said one of the biggest threats to the community is a "meth lab gone bad."

"The hazard to the community is the chemical fire," he said. "Last year, we had a house fire fatality that was possibly related to methamphetamine manufacturing. We've had a couple other house fires linked to it."

And it is not just adults who are caught in the consequences of a meth addiction.

The State Bureau of Investigations reported that children have been found to live in one out of four homes where meth is made.

One of the most popular ways to make meth is the one-pot method in which someone makes small batches of meth using a two-liter plastic bottle. About $45 buys all the ingredients, including the equipment to make meth. Pseudoephedrine, the active ingredient most commonly seen in Sudafed and other cold medicines, is the main ingredient in meth. A pack of the cold medicine, some batteries and ether, in addition to a handful of other supermarket ingredients, and someone can make meth in about 40 minutes.

"I can get everything I need to manufacture methamphetamine within a one mile radius of a grocery store or a hardware store," Peedin said.

Meth can be snorted, smoked, injected or swallowed in capsule form. Users and counselors alike say it's one of the most addictive drugs on the market. The high lasts two or three days -- unlike those produced by other stimulants like cocaine and ecstasy, which only last for a short period of time.

Even one encounter with meth is dangerous, said Dustin Shivar, a substance abuse counselor at Waynesboro Family Clinic.

Initially, taking meth increases activity in the pleasure centers of the brain, creating feelings of joy and excitement and making the users extremely productive.

But addiction begins almost instantaneously, Shivar said, and soon, addicts can no longer function without being on meth.

"Clients tell me that daily use over time has rendered them to where when they get up in the morning they have to have it to function. If they don't, they don't even have the energy to get out of bed. One lady said if she doesn't use, she'll sleep for two to three days at a time," he said.

Over time, meth depletes levels of serotonin and dopamine in the brain, both of which are pleasure-sensing.

"Users suffer from a psychological state where you don't find pleasure doing anything (if they aren't high). They just want to stay in bed, they don't have the energy and major depression sets in," Shivar said.

Ms. Kelly of Blue Horizons called coming off the drug "the ultimate bored."

"They were used to knowing this intense high, this intense energy," she said. "Now they just feel kind of listless. It's 'how do we set up life now that has any interest to it?'"

And unlike some other drugs, those effects can be permanent, even when meth is completely out of the user's system and he or she is no longer addicted. When a meth addict comes in for treatment, in most cases, he or she is put on an antidepressant, which many remain on for life.

"They end up very depressed when they try to stop. Most people that are successful in treatment have to go on antidepressants. They can't go through the time period of the crash because they are so miserable," Ms. Kelly said.

And recovery is a very long process, the counselors said.

"The initial goal is to get their mood stabilized," Shivar said. "The length of recovery depends on how long they have used that substance. It could take a year or two because of the severe depletion of serotonin and dopamine levels in the brain. Some research suggests it's an irreversible condition."

Shivar added that with daily use over time, it's nearly impossible to get back to "complete 100 percent successful brain function."

Meth addicts at the Waynesboro Family Clinic complete a diagnostic intake and it is determined if they should be treated on an in- or out-patient basis. If they need in-patient care, they are referred to facilities in Greensboro or Wilmington that offer that type of recovery assistance. Otherwise, they can be treated at Waynesboro or Blue Horizon as an out-patient. Both Shivar and Ms. Kelly say finding a support system and sticking to it is critical. Shivar works with patients on coping skills and impulse control, among other things, and highly recommends group meetings and getting a sponsor who is dedicated to helping the person recover.

But in the end, the addict must choose to beat his or her addiction, the counselors said.

"Most importantly it's up to the client," he said. "It's their responsibility to make a change."

Ms. Kelly said she likes to see patients at least three times a week and often recommends they get a hobby that creates an adrenaline rush to take the place of the highs they were feeling on meth.

To combat meth, the federal government enacted legislation in 2006, The Combat Methamphetamine Act. The law restricts the sales of non-prescription medication that contains ephedrine, pseudoephedrine or phenylpropanolamine, the main ingredients found in the over-the-counter medicines used to make meth. The law limits the quantity sold at retail stores to no more than 3.6 grams daily or 9 grams during a 30-day period. Stores are required to record purchases.

Peedin said although it might have put a dent in the amount a single person buys, methamphetamine "cooks" have found ways around the rules by having several users each buy a small amount of the medicine. He said what North Carolina really needs is more funding to combat the drug.

"What could help North Carolina is if we could get a state methamphetamine task force. Tennessee has it. If we had a task force like that we could start helping out with these dangerous mom and pop labs," he said.

Currently the Wayne County Sheriff's Office Aggressive Criminal Enforcement (ACE) Team has three members. The Goldsboro Wayne County Interagency Drug Task Force has eight members. Neither group focuses specifically on meth.

While funding for a methamphetamine specific task force might not be in North Carolina's immediate future, addiction counselors and members of law enforcement agree the drug is a problem in the area -- and its ease of production and highly addictive nature make winning this war on drugs an uphill battle, officers say.

"It's pretty alarming the size of shipments that come in," Wallace said. "And we're working every day to deter it."